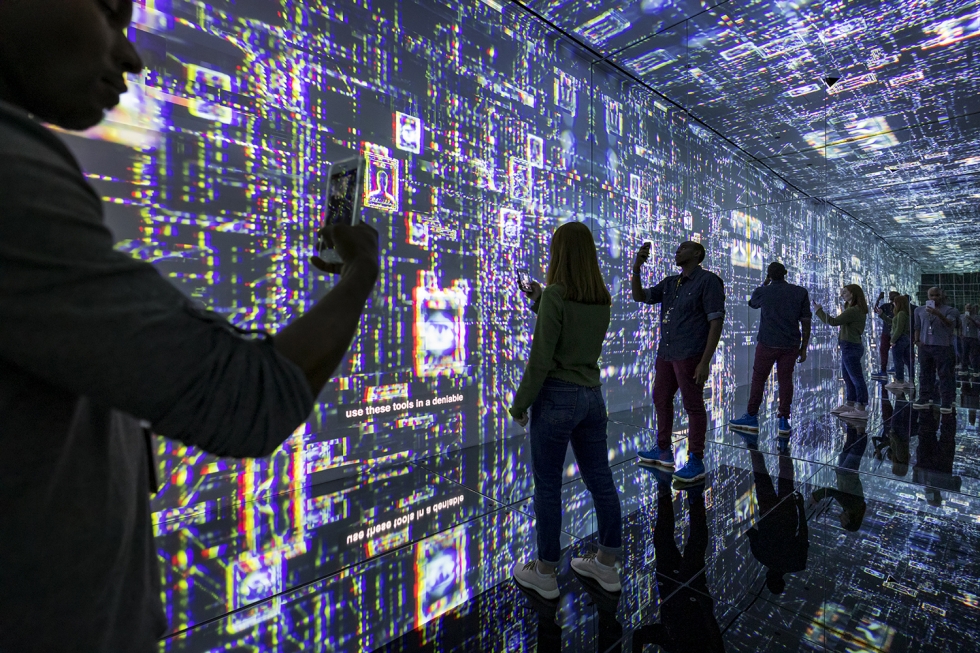

Espionage Facts

Peer inside the secret world. Learn the language of espionage. Hear about tradecraft—the tools and techniques—and some famous spies. You’ve heard the saying “knowledge is power”? Well, intelligence is in the knowledge business. Sometimes it might be useless. Sometimes enough to blackmail someone. And sometimes, just sometimes, it influences battles, sways governments, and changes the fate of the world.

We’re pulling back the curtain on the shadowy world of espionage, here are the Museum’s Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs):

What is a spy?

In the intelligence world, a spy is strictly defined as someone used to steal secrets for an intelligence organization. Also called an agent or asset, a spy is not a professional intelligence officer, and doesn’t usually receive formal training (though may be taught basic tradecraft).

Instead, a spy either volunteers or is recruited to help steal information, motivated by ideology, patriotism, money, or by a host of other reasons, from blackmail to love. From an intelligence perspective, their most important quality is having access to valuable information. For this reason, a government minister might make a great spy—but so might the janitor or a cafeteria worker in a government ministry.

Discover some fascinating spies in our Spies & Spymasters exhibit, such as celebrated dancer Mata Hari, who spied for the French during WWI and Mosab Hassan Yousef, a spy for Israeli intelligence.

Of course, the term “spy” also is used much more broadly, often to refer to anyone or anything connected to “spy agencies” (from intelligence analysts to hidden cameras), or any activity done secretly (spy missions, use of malicious computer software).

What is an Agent?

An agent is another word for a spy: someone who volunteers or is recruited to pass secrets to an intelligence agency, sometimes taking risks to spy on their own country. They may be recruited through money, ideology, coercion, greed, or for another reason, such as love (human beings are complicated). They trust their handler (a professional intelligence officer) to protect them. (You’ll find agents in other parts of government as well, but that’s a different use of the term: FBI agents and special agents, for example, work in law enforcement.

What is a Double Agent?

A double agent is essentially someone who works for two sides.

In the intelligence world, a true double agent is loyal to one side before being “turned” and transferring loyalties to the other side. George Blake, for example, joined Britain’s MI6 in 1944. But when communist North Korea captured him in 1950, he decided he was fighting on the wrong side. After his release, he continued to work for MI6 as he passed secrets to the KGB (including British and American plans for the Berlin Tunnel). True double agents are rare… because their survival is rare.

Outside the intelligence world, the term “double agent” is often used much more broadly to refer to someone who pretends to work for one side while secretly working for another, but whose loyalties remain unchanged.

What is the difference between a detective and a spy?

A detective or investigator works in the field of law enforcement, looking for clues and evidence (usually quite openly) as part of solving a crime. Think Sherlock Homes, or famed FBI agent Melvin Purvis who hunted down gangsters in the 1930s. A spy (or intelligence officer), however, gathers information (usually in secret) about the activities or intentions of a rival government or group in support of national security. Think George Smiley. or the Soviet Union’s Oleg Penkovsky who passed secrets to the CIA in the 1950s and 1960s.

What is intelligence?

The dictionary definition of intelligence is the ability to acquire and apply knowledge and skills. In the spying world, intelligence means information collected by a government or other entity that can help guide decisions and actions regarding national security. But intelligence can also mean the process by which that information is acquired (see Intelligence Cycle).

What is counterintelligence?

Spy agencies need to play defense. Counterintelligence activities, such as espionage or covert action, aim to prevent other spies from obtaining secrets, and to protect secrets and security against the efforts of other spies.

What is the intelligence cycle?

The intelligence cycle refers to the process through which spy agencies acquire information. It consists of at least five stages:

- Planning: Decisionmakers task an intelligence agency to acquire information on certain topics or specific issues of concern (“requirements”).

- Collection: This is where the spies, agents, case officers, tech ops, scientists, hackers, and others come in, acquiring information from different sources in a myriad of creative ways.

- Processing: Collected information needs to be narrowed down, prioritized, and put into some kind of digestible format. This might also involve having to decode information.

- Analysis: This is the stage where collected information becomes something useful that decisionmakers can use: intelligence!

- Dissemination: Intelligence agencies get the final product to the decisionmaker or “customer.” Of course, it’s quite possible that this might prompt more questions… and the intelligence cycle begins all over again.

What is espionage?

Espionage is defined as the act of spying or using spies, agents, assets, and intelligence officers, as well as technology, to collect secret information, usually through illegal means.

What is the Espionage Act?

The 1917 Espionage Act, passed shortly after the US entered WWI, imposed heavy penalties for spying or any activities that weakened or imperiled the country’s defense. In 1953, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were charged and convicted for giving nuclear secrets to the Soviet Union and became the first and only American civilians executed under the Act. Major parts of the 1917 Espionage Act remain part of US law today. In 2013, NSA contractor Edward Snowden was charged with crimes under the Act for intentionally revealing secret national security information.

What is economic espionage?

Economic espionage is the clandestine gathering of information from an economic competitor. Governments throughout history have stolen ideas, formulas, and technology to undercut rivals or “borrow” innovations. For millennia, China was a major target, with its silk, tea, and porcelain manufacturing secrets. Today, it’s the US—the world’s largest investor in research and development (R&D) It is often easier to steal someone else’s technology, for example, than to develop your own.

How do spies collect intelligence?

Intelligence agencies collect information in many different ways. The oldest method is through human sources (HUMINT or human intelligence), relying on spies and intelligence officers using their wits and talents (with support from Tech Ops). But when information is beyond human reach (or in places too dangerous or remote), technology is used to intercept messages (SIGINT or signals intelligence), conduct overhead surveillance (IMINT or imagery intelligence), or even sniff out chemical, biological, and acoustic signatures (MASINT or measurement and signature intelligence). Today, open source intelligence (OSINT) from non-secret, publicly available sources such as webpages and newspapers, makes up a vast amount of collected intelligence.

Find out more in the Stealing Secrets gallery.

How are spies recruited?

Spies are recruited via an approach or pitch by a case officer. This often seeks to persuade the individual through appealing to ideology, patriotism, religion, ego, greed, or love, or sometimes by using blackmail or some other form of coercion.

How do you get someone to risk their life and become a spy?

Persuading someone to put their life on the line is one of the hardest tasks for any intelligence officer. It takes training, patience, and empathy. Officers use a variety of approaches, based on the subject. A quote from Israeli intelligence officer Gonen Ben Yitzhak helps illustrate the point: “Recruiting is a very difficult art… understanding who the person is… his point of view, his background… then you know how to play with him.”

How do handlers cultivate trust with a recruited spy?

This depends on the specific individual to some extent. But some general ways to cultivate trust include using empathy, building a rapport (perhaps through shared friends, interests or dreams, or even shared frustrations), and showing vulnerability. Honesty (being open about who you are and what you want) may also be used—or, perhaps, false honesty.

You can find out more about the relationship between handlers and agents in the Spies & Spymasters exhibit.

How do spies go undercover?

Intelligence officers often operate abroad under some form of official cover, perhaps as diplomats in an embassy. Others operate without the protection of their government and must create a convincing cover that explains their presence and activities in a country—a businessperson, perhaps, or a student. The Russians call these officers “illegals,” the Americans call them “NOCs” (for Non-Official Cover). If caught, they’re on their own, and face arrest, even execution.

One of the undercover spies you can discover in the Spy Museum is Russian illegal Dmitri Aleksandrovich Bystrolyotov. Find out what happened to him in the Spies & Spymasters exhibit.

How do spies communicate?

Face-to-face meetings can be impractical, even deadly—especially if spies are caught red-handed passing or receiving classified information or carrying spy equipment. That’s why sharing information relies on covert communication or COVCOM. Methods include secret writing (such as invisible ink or tiny microdots) or sending and receiving secure messages using special technology (often concealed or even disguised to look like everyday objects).

See examples of COVCOM methods and devices in the Tools of the Trade exhibit.

Who was the first spy?

It has been suggested that the Twelve Spies that Moses sent to scout the land of Canaan, mentioned in the Book of Numbers in The Bible, might be candidates for the world’s first spies. But we know that spying was taking place much earlier than that. One of the earliest sources we have is the “Amarna Letters” from Ancient Egypt, which date to the 14th century BCE. They are diplomatic correspondence, recorded on clay tablets, that discuss among other things intelligence and espionage.

Was George Washington a spy?

No, George Washington was not a spy. But he was America’s first spymaster. During the American Revolutionary War, General Washington fully understood the power of espionage to outsmart and outmaneuver vastly superior forces. He employed spies, relied heavily on intelligence, and made us of codes and ciphers. He even hired Dr. James Jay (brother of “Founding Father” John Jay), to create a secure invisible ink.

What are some famous examples of espionage?

The Culper Ring

A network of spies active during the Revolutionary War, largely in and around Long Island, NY, that provided intelligence directly to General George Washington about Britain’s base in New York City. It all started in 1777, when Washington wrote a letter to Nathanial Sackett, a New York merchant active in counterintelligence activities. He offered Sackett $50 a month (more than $1,000 today) to spy for the Continental Army, plus another $500 to set up a spy network. That network would become the Culper Ring—and it helped steer the colonial army to victory.

The Cambridge Five

In the 1930s, five Cambridge University students—Kim Philby, Guy Burgess, Anthony Blunt, Donald Maclean, and John Cairncross—were recruited to spy for the Soviet Union. They went on to have careers across the British Establishment (including in Britain’s Secret Intelligence Service), where they had access to secrets they could pass on to their Soviet handlers. They undercut a number of intelligence operations and the effect of hunt for them—also known as a molehunt—led to growing paranoia in the UK and US intelligence communities.

The Russian Ten

In 2000, the FBI learned of ten Russian agents operating undercover inside the US. Some of them had been there for years. These sleeper agents (or “illegals”) were trained officers sent to the US to blend in, become American, and live what appeared to be normal lives…while secretly gathering information, cultivating relationship, and looking for recruits. For more than a decade, the FBI ran Operation Ghost Stories, keeping an eye (and an ear) on the agents and waiting for the right moment to close in.

Are spies real?

Yes! Spies are real. Or the International Spy Museum wouldn’t exist.

Are spy movies realistic?

Depends on the movie. There are elements of truth in spying that we see on TV and film, read in spy novels, and find in computer games. But in the real world, spying isn’t usually glamorous (it can be downright boring), it isn’t always secret, operations fail, gadgets don’t work, and there is no “license to kill.” That doesn’t mean spy fiction isn’t important: it plays a significant role in informing the public about the secret world of spying (accurately or not), shaping opinions and expectations. And sometimes, fiction doesn’t just influence popular ideas about spying—it actually inspires real spy agencies.

What gadgets do spies use?

So, so many. You can see many of them throughout our exhibit space. They range from the super high tech to the very low tech, but every one of them tells its own story.

What is cyber espionage?

Cyber espionage involves using computer systems to steal classified information, often government secrets. Those secrets might be sensitive data related to foreign policy, military technology, or even personal information about individuals. Espionage has been carried out for millennia, but technology has made it possible for hackers (sometimes sponsored by governments) to steal secrets quickly, silently, and with relatively low risk of being caught. Intelligence agencies, however, are increasingly aware of the cyber threat and are developing new counter measures.

Is cyber espionage legal?

During times of war, espionage against a nation is a crime under the legal code of many nations as well as under international law, and cyber espionage is no different. During peacetime, however, it can be a lot trickier to figure out when espionage crosses the line into illegality—all the more so for cyber spying. If cyber espionage does not cause any real-world physical damage, does it violate a nation’s territorial sovereignty? Where, in fact, does territorial sovereignty begin and end in cyberspace? These are just some of the questions being debated in international law regarding cyber espionage.

How much does a secret agent make?

Professional intelligence officers receive salaries based on their level of experience, like all government employees. Few own vintage Aston Martin DB5s and order beluga caviar on a regular basis.

Spies can earn a lot more money, though. In the 1980s, CIA officer Aldrich Ames received over $4 million from the Soviets for betraying US secrets, enough to buy himself a half-million-dollar home in cash and a flashy red Jaguar. But living beyond his salary aroused the suspicions of US intelligence, which ultimately led to his arrest.

How can I get a job as a spy?

If you are interested in working in intelligence, submit an application. Many intelligence agencies now have websites where you can learn about types of positions available and apply online.

Take part in the Museum’s Undercover Mission to find out about the skill sets involved in spying and test your own spy skills.

What are some words and phrases that spies use?

Test your knowledge of spy lingo with our Language of Espionage glossary.

How can I learn more about the world of espionage?

To learn more about spies and espionage, you can check out the museum's podcast Spycast, our YouTube channel, view our online collection, or attend a virtual event.